Why I Came Back to the Z80

My involvement with the Z80 predates the TEC-1 by several years. In the late 1970s, I was designing systems on paper. Most days I was working through the constraints of building a usable computer around an affordable processor. The work lived in the instruction set. The memory layout kept the constraints visible. Like many people at the time, access to hardware lagged behind understanding. The ideas came first; the opportunity to realise them came later.

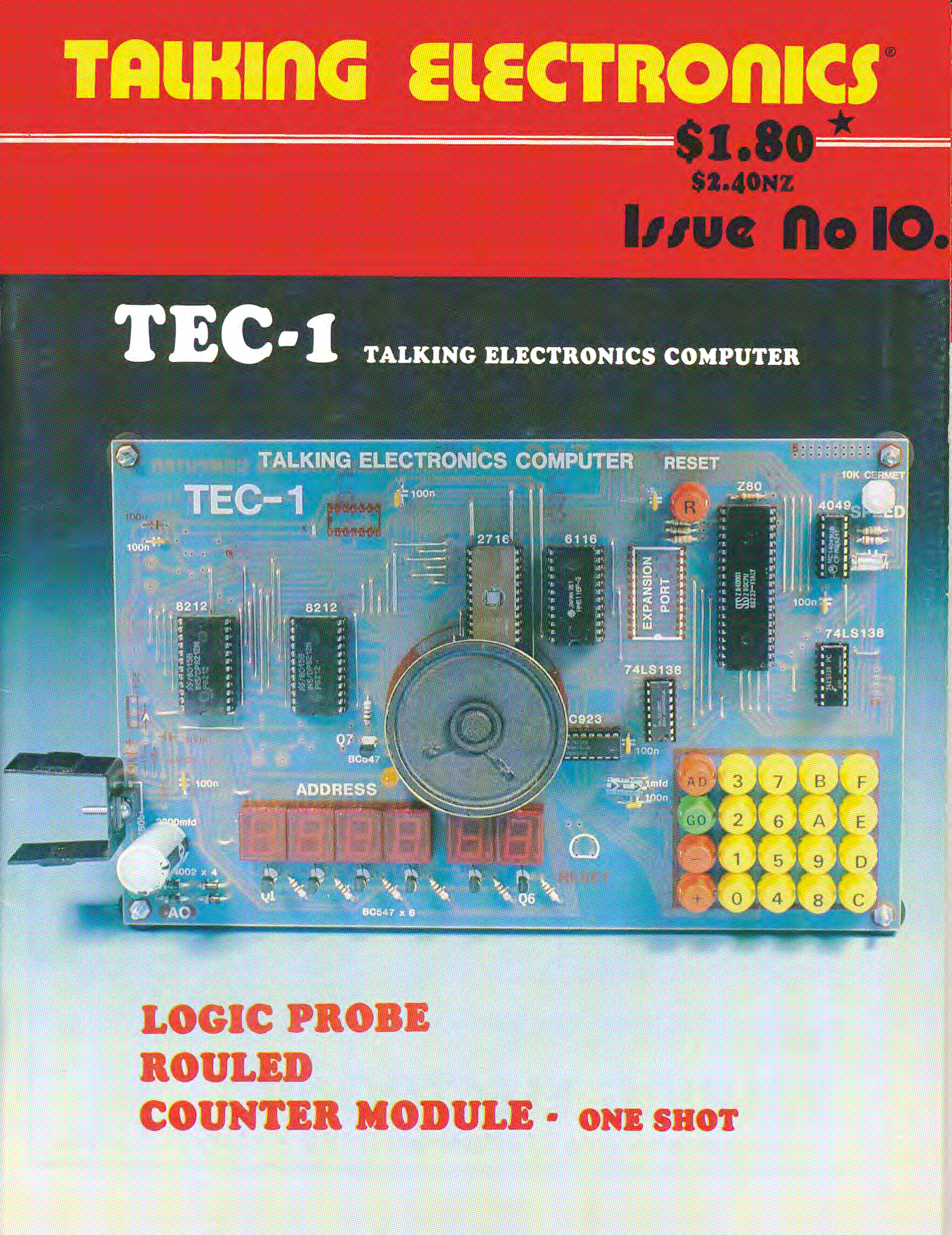

By the early 1980s that opportunity arrived. I built a sequence of Z80-based prototypes. I refined the hardware as I went. That work sharpened my sense of how people might interact with such a machine. Those prototypes eventually became the basis for a collaboration with Ken Stone, and together we produced the TEC-1 computer kit. Talking Electronics magazine published this kit in 1983.

The TEC-1 was a product of its time. The available components shaped it in practical ways. Hobbyists who prepared to work close to the machine shaped it too. It carried a long period of prior thinking about the minimal infrastructure required to make a computer programmable.

Working close to the machine

Programming the TEC-1 meant engaging directly with the processor. Input came through a simple hexadecimal keypad. Output came through a small numeric display. Programmers entered commands as machine code for immediate execution. Because storage remained minimal, the system encouraged careful and incremental work.

I wrote the original monitor software, MON1, to support that style of interaction. It provided controlled access to memory and execution while staying out of the way. Its role was to make the processor usable rather than to abstract it. Over time, users developed a working familiarity with the machine’s registers and addresses. Instruction flow became something they could reason about simply by using the machine.

The Z80 itself suited this mode of work. It was capable enough to do interesting tasks, yet sufficiently compact that developers could program and debug it without elaborate tooling. An assembler helped when I needed it. A symbolic debugger added clarity, but I could still work without that layer. The architecture was knowable and that mattered.

Returning with modern tools

When I began working on Debug80, I was not attempting to invent a new category of software. Debuggers and assemblers have existed for decades. Integrated environments have existed since at least the 1980s. Tools like Turbo Pascal demonstrated how effective a tightly integrated system could be for people who wanted to get productive quickly.

What prompted this project was a set of practical limitations I encountered while using existing Z80 tools. They did not align with how I think about programs or how I read listings. Rather than work around those constraints indefinitely, I decided to build something aligned with my own workflow. At the same time, the available platform had changed dramatically.

VS Code provides a mature, cross-platform environment with a well-developed debugging infrastructure. It runs across the major desktop platforms, and its extension points are well understood. Combined with my experience in JavaScript, it forms a practical foundation for building a debugger without reinventing the surrounding ecosystem.

Emulating the target hardware entirely in software is a natural consequence of that choice. I have explored TEC-1 emulation before, and extending that work into a debugger-capable environment follows directly from it.

Scope and direction

Designing Debug80 first and foremost centres on creating a working environment for my own use. It reflects my personal background and habits. I built it around the expectations I bring to a debugger. From there, it naturally extends to other Z80-based systems beyond the TEC-1. I expect it to reach other classic platforms over time.

The emphasis throughout remains on coherence and immediacy. I keep the number of moving components low so I can reason about a running system without losing visibility. Building ROMs for real hardware remains an important outcome, but it is not the primary driver at this stage. The focus here remains on understanding the system as it evolves.